As always I'm having qualms beforehand. I'm eight years older than I was last time I went to China with Eli. I suspect that means rough riding will feel even rougher. Sarah, Eli, and Joshua are all married now and the parents of infants. That means Eli and I are both leaving a fresh array of family members for a month. A whole month.

It started out as a two-week trip, then three weeks, then three and a half. The more Eli thought about the places he should go, the longer it got. When he finally made our reservations, the length of the trip had doubled. We leave September 16, if the Northwest Airlines pilots' strike is over.

Early in July, I asked Eli about our itinerary. He mentioned a few 36-hour train rides and two fifteen-hour trips. No way, I thought. A mere 24-hour trip wipes me out. For a couple of weeks I changed my mind several times a day, wanting to go, not feeling up to it, looking forward to it, then deciding I couldn't do it.

On July 19th, my voice teacher said to me, "I have alarming news for you!" She'd heard that Premarin, which I was taking, may permanently damage vocal cords. I haven't touched Premarin since then. Two weeks later I stopped taking Prevacid for acid reflux. And now, after a drug-free month, I feel almost like my old self.

There still are rubs however. Pauline reads the Chinese newspapers and has warned us that several businessmen have been murdered in China. Eli and I look more like backpackers than businessmen, but even Eli said that we'll have to be extra careful.

And there are the floods, forty million people homeless and probably desperate, epidemics, an unsafe water supply. I suspect this trip will tax my sense of adventure.

We would have left today if our flight hadn't been canceled. Instead we leave in a week. We're keeping the same return date, so we'll be gone three weeks, which is somehow less intimidating than four.

8:35 AM Beijing time, though we're not there yet, only halfway. Nine hours to go. That's the numerical data. Physical data: the lady sitting in front of me wears a perfume that makes my nose run. Otherwise I'm holding up well. Emotional data: the book I brought along is Bruce Chatwin's "What am I Doing Here?"

In 1985 someone asked how my trip to China had changed me. I said that China became a part of my life. That turned out to be an understatement. I now have a Chinese daughter-in-law and a half-Chinese grandson. For the past five years I've studied tai chi and Qi Gong, which I do four times a week. I grow Oriental vegetables in my garden, cook mainly with a wok and bamboo steamers, and use fresh ginger, soy sauce, dehydrated Chinese mushrooms, chili sesame oil, and rice vinegar.

Eli and Pauline import artifacts from China, Tibet, and Nepal; and Adolph and I often help out, or at least keep them company. Sitting in their stall or holiday store, surrounded by rubbings, batiks, antique pipes and pouches, carvings, jewelry, Tonka paintings, is like sitting in a museum, for everything's selected with an artist's eye. That's the problem. Eli, a serious painter, has to spend his time earning a living.

How does travel change someone? My first major trip, to Mexico in 1953, transformed me. It seemed incredible that the earth underfoot in Mexico was part of the same earth underfoot in New Jersey while everything else, the landscape, the people, their spirit, their lifestyle, their language, was so different. After that I learned to speak Spanish, to sing mariachi songs, to dance Mexican folk dances. I hung out with Latinos and identified with anything Mexican. It changed my sister even more. She's been living there for the past twenty years.

If I had never been to Mexico, I doubt I would have gone to North Africa alone when I was twenty. That trip introduced me to myself and reinforced that pennywalk route I always follow.

2 AM, I'm in a Beijing bed and thinking that my trips build on each other, a giant research project into life. They go nowhere in particular, motivated by a curiosity about people who are as different from me as possible.

...We're in a taxi heading to a wholesale market, passing bikes that go in both directions though this is a one-way street. Our driver says almost nothing in Beijing is the same as it was when I was last in this city in 1985, new buildings, many more cars and motorcycles, of course more people, fresh trees planted. The sidewalks here are bicycle parking lots.

At 6 AM I went on a tai chi quest. The area around the hotel was alive with vendors set up to sell breakfasts, people pedaling to work, waiting for the bus, running, striding, shuffling. Somehow I hesitated to ask directions, and my first attempt told me why. "Tai Chi?" I asked the sentry at a construction project, figuring he'd catch on, since tai chi is, after all, Chinese. He stared at me blankly. I tried someone else, adding gestures, and finally tried a group of women at a bus stop, adding still more gestures. One of them said, "Ah, tai chi chuan!" I then attempted to decipher the return gestures, which indicated I'd chosen the wrong direction. I walked for several blocks and found a footbridge over the highway. Good, that clarified the arching movement of her arm. I crossed that and came to another footbridge that doubled as a small and colorful market as it spanned a filthy river. Okay, now which way? I picked the least traveled road, more likely to have a park, and it did, an idyllic park with ponds and weeping willows, and people: walkers, runners, stretchers. However I was on the wrong side of a cast-iron fence. I walked further and further, block after block, expecting an entrance. I didn't find one.

...Now I know why oriental skirts have slits; it's so the women can bike. Our taxi driver says it's dangerous to drive in Beijing, too many bikers cutting in.

...And now I'm in the wholesale market, watching retailers with suitcases and luggage carriers. I'm the bearer of the photos, and the vendors who knew Pauline was pregnant are anxious to see the baby. Otherwise I sit on very low stools and silently watch as Eli sizes up the merchandise, works out the price with the vendor, fills his giant backpack, then goes on to the next little shop.

On the plane I read the latest issue of the China Daily, the Chinese government's English language newspaper, a whole page about the floods, from the viewpoint of individuals who lost crops, homes, livelihood, and greatly appreciated the government's help. A feature article told about the brave man who risked his own life to warn everyone in his village of an oncoming surge of water. Every article had its message.

5:25 AM, still dark. We've been up since four, and I'm waiting patiently for dawn so I can figure out how to get into that park.

We both have colds or allergies, we're not sure which. First there was the dry, recycled plane air and perfumes, then the constant smog, the dust, the mildewy hotel. My throat is sore, my nose hasn't stopped its downhill drip, and we've already used up one roll of Kleenex toilet paper on our noses.

...now I'm in the middle of another wholesale market. Eli's backpack is already so heavy I can't budge it when he puts it down. He's bargaining with a Hmung woman who remembered him from southern China last year.

Last night I sat down on the couch in the lobby to write. The girl in the chair next to me hissed at a passing male. I glanced at her thickly-smeared lipstick and crotch-length skirt and thought, hmmm, this should be interesting, but all she had in mind was a light.

The hotel restaurant becomes a karaoke bar at night and the voices of aspiring singers are electronically transported to every ear on the ground floor. That added noise pollution to the second-hand smoke. Finally the woman stubbed out her cigarette, left, and I finally took my pen and pad out of my purse. A young woman leaned over me, "Where are you from?"

"America."

"Oh good!" She had a list of questions to answer in English, based on texts by Erich Fromm and 18th and 19th Century French philosophers. She's Ling Tao, an English teacher from Mongolia, here to upgrade her skills and to take care of her father who has a brain tumor. He's being treated at a nearby cancer institute and has already improved dramatically.

She sat close to me on the couch, peering into my face as we talked. I'd inch away; she'd catch up. She had no sense of others' space. And why should she? The signs of overcrowding are everywhere, people bumping, elbowing, shoving, broad sidewalks made narrow by barricades of bikes parked three-deep; cars, bikes, and pedestrians competing for the right of way at crossings. I think I'll never learn to get from one side of busy streets to the other. Eli said to stop if it looks like they're really going to hit me.

Ling Tao is a perky, round-faced beauty. Her parents are from two different minority peoples, and she speaks both of their languages, plus Mandarin, and a flowing English.

When I returned from my tai chi quest yesterday, I noticed a footbridge over the highway right next to the hotel. So this morning at 5:45 I crossed that bridge, sure it would lead directly to the park entrance. It didn't. There was no way to get across the river. I followed a semi-deserted path along the water's edge towards the bridge I'd crossed before. I could hear the occasional yells of a man whom I'd seen yesterday in an isolated spot on the shoreline. He'd exercised and shouted, then pedaled away on his bike, still emitting regular bellows. Either a nut or a practitioner of some kind of Qi Gong for the voice, I'd thought. Today I knew the latter was true, for several distant male voices echoed back over the water, making my walk seem surreal, as if coyotes were howling in a forest in the middle of Beijing.

The second footbridge, mainly for pedestrians and bikes, was a market again today, turnips, leeks, leafy greens, sweet potatoes, long, fat string beans, cabbages, dill weed, carrots, pears, fish, a pile of gleaming liver, live chickens squeezed into cages, most of the wares spread out on the ground.

Once across, I went straight, aware that to the left I'd find uninterrupted fence. I kept going, began to get nervous, asked a man loading a truck about tai chi. He and his friends laughed at me. Then there they were, crowds streaming through a gate. People were exercising in the bushes, along the edges of ponds, on paved playgrounds, though no one was doing tai chi at the moment. The howls echoing over the river a little earlier were minimal compared with those in the park. The air vibrated with human sounds, howls soaring over the ponds, female voices as well as male, rising through willows, bouncing against eccentric rock formations, heeeeeeeeeeeee, huh huh huh, sometimes chaotic, sometimes in response to one another.

I crossed a footbridge over a pond, one flight up, one flight down, onto an island, found a large group doing Qi Gong, hung my sweater on a fence, and tried to follow. Two women rushed over to help me. They adjusted my fingers, my hands, my arms, made sure that I bent and unbent my knees at the proper times, that my tongue was touching the roof of my mouth with my teeth slightly apart. Then I noticed it was already 6:40, and I'd promised to meet Eli for breakfast at 7. When practicing Qi Gong, it's important to finish up properly, never to simply stop in the middle, so I understood my instructors' reluctance to let me leave. But I left. As I fast-walked out of the park, I saw a group doing tai chi and decided that tomorrow morning would be mine to spend in the park.

Ling Tao accompanied me to the park today. She was a delightful interpreter, most of the time. When we first arrived, about a hundred people stood ready to do the 24-part tai chi form. Ling Tao asked if I could join them. I thought the space between two women in the front row was large enough for one more, but one of them stepped out when I stepped in. Then two strong hands clasped my shoulders from behind and moved me to the left. I turned around and saw a perfectly straight line of people in back of me, looked down and saw a chalk grid drawn on the ground. Everyone was evenly spaced in both directions. We did the form twice, the same way we do it in Milwaukee. Here I was, floating in from the USA and suddenly part of a group phenomenon in China. I loved it.

When we finished, everyone gathered around the master, a woman, to discuss the fine points, just as we do back home. An old man complimented my form, someone else asked how long I'd lived in Beijing, others spoke to me in Chinese. Ling Tao told me they'd be doing that form all morning. That's when I found out that I hadn't stepped merely into a group of people doing tai chi, I'd stepped into a rehearsal! They'll compete in Tiananmen Square in October.

The form I really wanted to do was the forty-eight. We wandered the park path, Ling Tao asking passers-by and exercisers where people do the forty-eight. A young man was doing a form that resembled a dance, and his face, body, and movements captivated us. Ling Tao tentatively echoed his gestures, and soon we were both following him, smiling at each other as we rippled under the trees. When he finished, he was pleasant, but ordinary compared to the flowing figure we'd been imitating. Ling Tao asked him where I could learn his style of tai chi, and he pointed to his master several yards away.

She then asked the master to teach me his Chen style tai chi (I do Yang, the official style of the Chinese government).

"If you come every day for about two years, I'll teach you," he replied. He did lead us through a short routine. Whereas in Yang style we look at our palms, in Chen we looked straight ahead into space, in anticipation of the next movement of the hand. He emphasized the alignment of head, back, butt. Somewhere along the way Ling Tao mentioned to him that she's a runner and has pains in her shins and gets headaches. He told her to stop wearing those high-heel shoes, to stop running, and to start doing tai chi and Qi Gong. Their exchange gradually became more intense, and the more intense it became, the less Ling Tao translated for me, "It's very involved, I'll explain it all later." It finally occurred to me that I didn't have to stand and watch. I returned to the people practicing the twenty-four.

She caught up with me ten minutes later, very excited about the Chen master. He'd told her some important things. "In this society where there's so little space and people bump into you or knock you and don't even say excuse me or I'm sorry, you should take things calmly. If someone hits you, don't hit back, and then he will be ashamed and lose face and you might even become friends."

We walked around the park filled with families out for Sunday strolls.

Ling Tao's boyfriend is three years younger than she is. Of course he didn't tell her that at first, for in China women don't go out with younger men. He studied to be a school teacher, then became a journalist, and now is going into business. "He thinks too much about making money, and money shouldn't be that important."

They've been dating for six years, and plan to get married, but not right away. "My sister lives in Japan, and I want to study there for two years. If we get married, my boyfriend won't let me go."

"Don't you want children?" I asked.

" I want to raise children who have no parents."

"How many?"

"As many as I'm able to."

"How does your boyfriend feel about this?"

"He wants his own child."

6:50 AM. Baggage in taxi, we waited 25 minutes for the hotel clerk to reach the Master Card office to okay my charge, finally gave up and paid cash, then headed for the train station, Eli as usual in front having an intense conversation with the driver, both of them laughing. I picked up on Green Bay Packers, Milwaukee Bucks, Harley Davidson, and Taiwanese wife.

Eli said last night that Adolph and I can show Isaiah China while he and Pauline do the buying next year. I said no way, I wouldn't even cross the street with that baby.

We arrived at the new Beijing train station, an extravagant structure at least a half-mile wide, I got out of the cab, then found myself waiting and waiting while Eli and the driver continued to chat. Afterwards I asked, "Hey, Eli, why'd you exchange addresses?"

"He's a good guy. He has a baby the same age as Isaiah, we'll go out for a drink next time I'm in Beijing."

It wasn't allergies. Eli and I have sniffled and coughed ever since we're here. First my nose was a faucet. Now the drip's fixed, but I can't breathe, I've a red throat and chills without fever. The past two nights we've taken naps before dinner, then haven't gotten up, which actually is good for me. I feel much better on an empty stomach. We're traveling soft bed, comfortable, isolated, just Eli and me and two roommates. It's a lot easier to survive long trips this way. On the other hand, this morning I felt trapped in the sterile section of the train, slept on and off, read "What am I Doing Here?", which didn't answer that question, and why should it, snacked on corn flakes, prunes, pumpkin seeds, and noodle soup, sucked Ricolas, and wrote though I wasn't in the mood to write. Finally I got up, combed the stringiness out of my hair, did tai chi in the narrow corridor, then took a walk through the first car of hard seat. I longed to photograph the beautiful heads, light hitting cheekbones, most tilted back with eyes closed, framed in blue by the straight, high-backed seats. But then I'd be the American coming from first class to photograph third, and frankly just walking through hard seat made me feel like a voyeur, which in a sense I am. For that matter, I am even at home when I write about what's going on around me. Writers and artists have automatic voyeur status.

We can't turn off the sound, so here's a Chinese version of Auld Lang Syne. Our roommates are a thirty-eight-year-old married businessman and a twenty-four-year-old single woman; they work for the same firm. Pretty liberal arrangement for China. 4:10 PM, only 26 hours left of our 33-hour pilgrimage to Xining, getting closer and closer to Tibet, where we're not going. Not enough time. The landscape has been flat, but we're getting near the mountains, ah, intense green fields, reaping time for some crops, planting for others, some fields burning...At the last stop the businessman got off and bought food, and now the young woman is trying to open a thick plastic bag in which a barbecued chicken is vacuum-packed. According to the label, the bird's been in there five days. They're very attentive to one another. A little while ago I looked up and was surprised to see his body spanning the compartment, legs on his own bed, torso on hers... Crossing the Yellow River now, first an expanse of brown water, then an equally large expanse of mucky river bed.

We're pulling into a city, piles and piles of red and greenish bricks, a lot of construction going on. A stout middle-aged woman sitting on a tiny porch, ramshackle houses, bricks holding down tar-paper on roofs, windows broken, someone facing seediness night and day. Now fields. Long rows to hoe.

...It's noon, only six hours left. China has been streamlining its train system, and this train is new, clean, and fast. I've slept half the time, and my cold's much better. Railroads often follow rivers, and we've been following dry river beds. The Yellow River has been drying up in winter ever since 1978, when all the trees were cut down.

The mountains here are rock, streaked red towards the bottom, tan on top. We passed the flat, dry land long ago. Between Lanzhou and Xining, there's water, a wide brown river, so the green plots of cabbage and leafy vegetables no longer seem surprising.

We're only two hours from Xining, the capitol of Xinghai, a province that borders on Tibet.

We've arrived, and just as I was thinking this city is ugly but interesting, our taxi driver told Eli about a market forty minutes away. We're going directly there, Eli in front with the driver...We're in China five days, and we're now two days by bus from Lhasa, much less than that from the Tibetan border. Lhasa is closer than it sounds; the trip is long because the roads are bad. "Do you want to go to Tibet?" Eli asks. "Whatever you want," I reply. Of course we don't have time, two days there, two days back. This cab ride is one of the bumpiest rides I've ever had, and the dustiest, like riding through a heavy fog in intense sunshine. The road is about to be paved and piles of paving materials block the way and dust the air. Roadside vegetation is coated with grey, cyclists come at us in a dream. The ride's so bumpy because this is a bread car, a mini-mini-van shaped like a loaf of bread and worth about as much, and as sturdy as a bread box.

Now we're stopped altogether. Our driver gets out to check. He returns. "They close the road one section at a time while they work on it, it won't be too long," Eli tells me.

This is a heavily Muslim area, and our driver is Muslim. He just got out again. Bikers squeeze past all the waiting vehicles. I can't imagine pedaling through that dust fog nor over all the stones. He came back. The problem's a truck caught in a gulch. He's upset, pacing back and forth outside, puffing his cigarette, a slight man with glasses, surely sorry he told us about the market. Ah, motors are starting up, we may be going, may not be. Our driver sighs. His meter does not register time, only distance.

...We're moving, sort of, no one's letting anyone in. Now we're stopped again. "His car's got a problem," Eli says as the taxi stalls for the third time. It's probably clogged with dust. The driver and Eli get out and push. The goddamned motor's not turning over, and I can't stop laughing as we create the next traffic jam. The engine of a bread car is in the back seat, right in front of me, phew, what fumes. He's trying unsuccessfully to fix it as all the other traffic passes us by. Ahh, the motor turned over. And now that he's got it fixed, the traffic's stopped again. This forty-minute trip is taking two hours.

The driver speaks a Muslim language. ...Now we're moving, bouncing, bumping. China has no time zones, so it's after seven and still light, which is lucky. I don't care to go on mountain roads in the dark. We're cruising along the smooth highway on our way to a Tibetan village, cruising so fast I'm looking back with nostalgia on the traffic jam, going upwards, fall colors in the mountains. Now going downwards, picking up speed.

5:30 AM. Yesterday was not a writing day. I woke up before 4:30, which I did again just now, and waited for sunrise. It's dark here from about 7 PM to 7 AM, very very dark. Even in the hotel. Perhaps they're saving on electricity by leaving hallways dark and not fixing broken switches. They're not saving on water though. Our toilet runs non-stop. "Pretend it's a brook," said Eli. They're definitely saving on heat. Right now, sitting in bed, I'm wearing four layers of silk, an acrylic sweater, a nylon slack liner, and cotton socks and underwear, my legs covered by a quilt, yet I'm not too hot.

We might be the hotel's only guests. It's hard to know in the dark, and we weren't here by day. Around 6 AM yesterday I thought I'd write in the lobby, left our room, and walked into blackness, unlit corridors, hallway, staircase, lobby, not that I got down there. I returned to the room, grabbed my flashlight, and tried again. I got to the top of the staircase. The place felt creepy. Again I went back to the room. Eli said to look for the light switches. I tried again, found one at the top of the staircase, and went down to the gloomy lobby. Near the entrance, the clerk was on a couch, sound asleep under a quilt.

The outside gate was padlocked, but I did tai chi in the driveway as the sky slowly brightened to the sound of eerie, unfamiliar bird warbles, occasional calls for prayers by monk voices and prayer horns, once in a while a motor, that's all. Around 7:30, the town largely somnolent, Eli and I wandered past the monastery buildings, closed till 8:30, and sized up the two main streets, lined with hundreds of shops selling mostly Buddhist-related artifacts. After a breakfast of sautéed vegetables and noodle soup, we shopped from 9 AM to 5:15 PM, going into and out of dozens of tiny shops. Roving peddler women were selling necklaces with holograms of the Dalai Lama. "Amazing. A few years ago they would never have been allowed," commented Eli. He made the mistake of buying some from one woman, and then came the deluge. Every peddler in the vicinity shoved Dalai Lamas in our faces, at least twenty women fighting to get near us, Eli insisting he'd had enough, though he kept buying more. We ducked through an open door, and they followed. A whole side of beef lay raw on a table. Where were we, anyway? A butcher shop? No, a restaurant! I certainly wouldn't want to eat there. We left. The women continued to harass us, some following us into every shop. Though Eli doesn't believe in being nasty, I turned around and snarled, "Get away, I don't want your necklaces!" It worked.

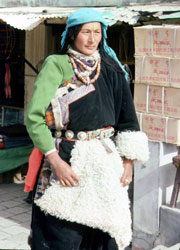

We continued along the hillside streets unimpeded, checked out prices, later returned to buy, on this grey, sometimes drizzly, always cold day. Many of the vendors were Tibetan. Warmth, beauty, shyness...that doesn't mean they'd give Eli the price he wanted. I'm merely the observer, listing purchases, occasionally giving an opinion, as the backpack gets heavier and heavier. I'm glad Eli does pull-ups and push-ups (even on the train using the handrails of the upper berth) and lifts weights. And speaks fluent Chinese. It's as if he's been in training for heavy-duty wholesale shopping in China.

Every cute little boy makes me think of my Chinese grandson. Ling Tao had asked me if Eli's son looks Chinese, so I showed her some photos. "Oh, Chinese, Chinese, he's Chinese!" she exclaimed. I wondered why she cared when there's already over a billion Chinese people. It's I who cares, who relates differently to the country when part of my family is Chinese.

At night the village was almost too dark to go outside. I used my flashlight so I wouldn't fall off curbs or into holes. I suggested we eat at the first place we came upon. It had three large round tables, only two with cloths. After we'd ordered, Eli said, "Remember this place? We ducked in here trying to escape from those peddler women." He was right. The table without the cloth was the one that had held the side of beef. The place felt contaminated, but we ate there, while everyone else, both adults and children, seated at our table and the other usable one, watched a Chinese super-hero video. The heroine was a beautiful oriental woman; the evil sorceress was a blond westerner. When the video was over, they rewound it and played it again.

"You know, it's very strange, I can look at people and tell how many kids they have," Eli is saying to me, "And I can usually tell the sex." It's 8 AM, and we're in a taxi to Lanzhou, Eli up front with the driver.

"This guy doesn't worry about oncoming traffic, does he?" I say.

"That's the way they all drive, in the center. If they see someone coming, they move to the right," Eli replies.

Damned if I'd ever talk to any driver under those conditions. I'd make sure he concentrated on the road. Eli offered to let me sit up front where it wouldn't be so bumpy. I'd be a nervous wreck. And the driver would probably be turning around to talk to Eli.

...Going through Xining, beautiful Muslim temple being refurbished...Out of Xining, "Ooh," I say, "I don't like passing on curves."

"Yeah, they have a habit of doing that..."

"Wow, look at those mountains."

"That's what we'll be going through."

"I know," I reply, no joy in my voice.

Eli said if all goes well we'll arrive by one. I'm already hungry. Nothing in the monastery village, not even the hotel restaurant, was open before 8, so breakfast wasn't a possibility.

First we pass on the left, then on the right, flatbed bikes, tractors, mini-buses. Driving here is a weaving game. A toll booth, maybe tolls will keep the traffic down. There's a newly-paved two-lane highway between Xining and Lanzhou. Damn, this driver speaks with his hands, and we're in the mountains. I should engage Eli in conversation so he won't talk to the driver.

...We just swerved around a herd of sheep. Farming village that reminds me of Nanwutai, truckload of butchered goats. What makes me think they were goats? Our driver never lets anyone stay in front of him for very long. This road follows a brown river. "He says the water is not very clean," Eli tells me, "You can't eat the fish." New car, new road, but boy am I getting bumped...Whoops, wide bus coming at us, our driver swerves again.

The driver stops and opens the door for me to get out and go to the WC. Sweet of him to think of that. I assure him I don't need one. Nothing has entered my mouth today except for a few sips of water, which is just as well since I'm sure anything would only bounce back up.

"See them trying to get that sheep back into the truck. He must have fallen out," says Eli. The truck is squeezed full of bighorn sheep, very woolly. I hate to think of where they're going.

Piles of wheat in the middle of town. 9:22 AM. the driver says we'll arrive 12 at the earliest, 1 at the latest. Our driver is very nice, reminds me of Jimmy, my tai chi master, who's from Shanghai. He's a good driver, under the circumstances. Tomorrow we have a seven-hour drive.

Lots of oncoming trucks, vans, and buses. Most of the trucks are royal blue pick-ups with wooden sides. More roadwork...Lots of repaving, lots of house construction everywhere we go. Now we're on a smooth new road again.

"180 kilometers to go," Eli says. Our driver's native language is the Xining dialect. Green fields...Villages with mud walls and mud brick houses... Donkey cart...flat-bed tractors...big, modern hotel in a very small town. Strange location. The driver can't think of any reason for people to come here...

It's a holiday, the birthday of Sun Yat Sen. Cars pass with the "just married" red ribbon. Here's a marriage cavalcade, cars, vans, and buses.

My ears feel clogged, we're very high, earth red... 10 AM...We're passing two trucks, two bikes coming at us, our driver honking, cyclists moving towards the shoulder. Whew, they survived! Another village, we toot right through. Oh my god, we almost hit a tractor cart. I wonder if the teaching method in schools, memorizing great amounts of material, increases powers of concentration and makes the Chinese better-equipped for this driving mode, accelerate, peer ahead, then either slow down or accelerate some more, constant slowing and speeding up, constant watching for the oncoming traffic.

"Guy stopped on a curve to take a nap. Did you see that?" says Eli.

We go around a pile of stones, "Avalanche," says Eli.

We're going along the brown river again, very silted up. Mountains barren. Our driver sneezes. Lucky we aren't going around a curve. Stubby green growth on the mountains, like five o'clock shadow.

"Do they have cars like this in America?" our driver wonders, and Eli says, "No." These bread cars would never pass inspection in the States. If we had heavy cream, it would come out whipped. In Beijing the taxi fares are determined by the type of car. The bread car is the cheapest. Wuhhh, hit a big bump, "Are you okay, Mom?"

"That's a cotton factory," our driver tells Eli... Big city in the valley below. All the buildings, even the largest ones, are the same brownish grey as the earth. ..."We're in Gansu province," he tells us.

"The air is very clean up here," Eli is saying, "...and very bad in Lanzhou."

"Well, we'll stay inside," and I'm only half kidding. The mountains are more and more spectacular, sun glittering on brown river. I'd love to take a photo, but don't want to ask the driver to stop... Now Eli asks him to, and he buys a bag of apples.

We're an hour away from Lanzhou, and it's 11:45. I almost took a great photo, then we hit a bump. But what's a photo of a mountain range, anyway, especially of these mountains, so impressive in their expanse. It would be like photographing the Grand Canyon from the floor. The canyons here, combined with the mountains, are as startling as the bumps in this bread car.

Here's the brown Yellow River again.

A lot of houses are built these days with a white ceramic veneer over bricks. 12:28, a major highway with center barrier, no more peekaboo. Eli's sound asleep. More and more urban now. and the urban is spreading, block after block of public housing going up. I've never before seen so much construction.

Our driver was at the hotel a half hour early this morning to take us to our next destination, a village in the mountains five or six or seven hours away. We specified no bread car and have a nice new sedan with only fifteen thousand miles on it, which should make our trip much smoother and faster, better car, better speed. The front seat has the first usable seat belt I've seen in China, back seat belts removed, or more likely never installed. Perhaps the driver loses face if a passenger feels he needs one. No infants seats here, and Eli wants to bring Isaiah sometime soon.

I've yet to see a bike helmet in China.

We left the hotel an hour ago, and we're still only a few blocks away, trying to get train tickets for Canton for Monday, a forty-hour trip, just in case I thought 33 was long. At least my cold is almost gone. Eli and our driver just came out of the ticket office. No way to get tickets today. The go on sale three days before departure, and we want to leave in four days.

"See, when traffic is tight, you can drive on the sidewalk," Eli is saying as we drive on the sidewalk.

Our driver has never been to the village we're headed for, so he and I will look around while Eli shops. Eli just warned him that if we go into the mountains to be careful of the packs of wild dogs. Of course we're not headed anywhere yet. Except to the house of a friend of our driver so Eli can leave money with him to buy our train tickets when they become available tomorrow...

10 AM, finally on our way. Our driver's name is Zhen...here's a Muslim temple, very modern style. Another Muslim temple coming up, an old one with a fantastic relief on the outside, graceful minaret. You can tell Muslims by their round white caps. This section of Lanzhou is a wood market, fifteen foot boards and uncut trunks leaning against buildings, then a couple of blocks of furniture for sale, couches, chairs, tables, heaped on the sidewalk, and now out of the city, crops growing on terraced foothills, whew, and here are the mountains, high ones. Of course we're already high. Lanzhou is 1600 meters above sea level.

Zhen's car is manufactured by a Chinese-French joint venture. This trip will be long: Zhen's going at a relaxed pace. We've bought him for three days; he has no motivation to rush. Also the roads are wet. Zhen is different. He doesn't turn to look at Eli when they talk, but most vehicles are trucks, which go more slowly than cars, so he's passing constantly. Fall colors, yellow orange red, tiny trees, probably about two feet tall... the mountains here are cliff-like. We just made a pit stop, and as I looked down the rectangular hole in the ground, I realized I was on the edge, that if I stepped into the hole, I'd have a long trip to the piles below. I was in too much of a hurry when I went in to notice that if I overstepped, it'd be a big overstep.

"This is a rainy non-market day and everyone's inside. What isn't inside are the brilliant yellow, almost orange bunches spread out on roofs and walks and on the tops of walls. I first thought it was squash and Eli first thought it was bananas. On closer view it's corn. Zhen says once dry the corn will be ground up for flour and corn starch. Piles of husks drying out in the rain. They're used to start fires for cooking. The horn is still a major accessory in any vehicle, used whenever there might be anyone who should be aware we're coming through.

Muslim village after Muslim village... We're suddenly in dense fog, "Oh, you're missing your view here," says Eli as we curve around the hairpins. In the hill towns, it makes sense to cruise down the middle of the road since there are lots of bikes and pedestrians on the sides of the road and very few cars.

Big city. In. Out. Road now completely blocked by a herd of long-horned sheep..."Boy, Eli, look upwards! It just keeps going on and on..." Sheep dotting the mountainside. I've never before seen mountains like this, intense autumn colors going all the way up, and these mountains are high. "See, you've got another satellite dish there," Eli is saying. Television has certainly arrived throughout China.

Every time we round a curve, there's a fresh layer of mountains, rockier now, less of those scrubby, colorful trees.

Villages around here are Tibetan, judging by the dress, hundreds of photos untaken...A tractor cart filled with people, including a monk, purple robes flying, shakily crosses a swaying wooden bridge. Our only stops will be for the WC, and I'm waiting impatiently for that.

Here's a fork in the road, and the police are stationed on an island in the middle. Now they've stopped us! They're checking Zhen's i.d., now checking our luggage, now arguing with Zhen...I don't know what's happening. Eli's getting out...Two buses just narrowly missed each other...Zhen is very upset. What the hell is happening? He's shouting at them, and he's a pretty calm man. Eli is patting his back. They've stopped a truck loaded with goats. They let the truck leave, and we're still here. I wonder if we'll ever get to the village we're headed for. Eli's taking money out. It must be a shake-down.

"How much was it?" I ask Eli, when he returns to the car.

"Three hundred yuan fine. They keep rewriting the rules, the corrupt fucks," he replies.

Now we're moving again, and Eli's discussing the incident with Zhen. And I'm thinking the poor guy works for three days for a thousand yuan, then loses three hundred yuan to the police, we should help him out.

I suggest it to Eli. "He says he'll get the money back, it won't be a problem. They claimed his paperwork is wrong. He says nothing was ever sent to him. When he gets back to Lanzhou he'll go to the police station..."

Yaks grazing at the roadside... "Avalanche area," says Eli.

"Sure as hell is," I reply, gazing at the trail of rocks on the hillside...the bus in front of us almost hit a cow. Goats are all over the mountainside.

"At first you don't notice all the buildings on the mountainside," I say. They're exactly the same color, made from the mountains. I'm hungry. Seven and a half hours since breakfast. Eli tries to give Zhen a banana, but he doesn't want to eat while driving! Thank you, Zhen.

This is sheep territory, dappling the road, startling white on the mountainside. Five kilometers to go...

1:30 AM This a mainly Tibetan village, a monastery town 3000 meters above sea level. The sloping main street, the only street I've seen thus far, is lined with shops selling Buddhist-related objects, road and walks flowing with purple-robed monks, with Tibetans in their native garb, with various other Chinese inhabitants and tourists, and occasional foreigners. In every direction, there are mountains. It's also goddamned cold, in the 40's inside and out. My layers for sleeping are five of silk plus my sweater plus two blankets. I'd probably still be asleep if I hadn't consumed cup after cup of Eight Treasures tea, a tea with eight different kinds of fruits, seeds, and berries expanding in hot water while the lump of rock sugar gets smaller.

Later. Eli said he'd finish his shopping around two or three and meet me back at the hotel at five. It's now almost six. Where the hell is he? Not that we're doing anything this evening. Certainly not eating. Our breakfast was a half meal, unless you like rice gruel, with side dishes of fermented tofu and cabbage in chili-sesame oil.. Our lunch, big enough for two meals, was at a Tibetan restaurant. Eli ordered the only Tibetan dish: the waiters brought him a slab of yak butter, told him to douse it with grainy sugar, pour hot water on it, dump in wheat flour, mix it with his index finger till it's the consistency of dough, lump it and eat it with his fingers.

As we ate, the usual television set going strong, some monks came up to the second floor restaurant asking for money in exchange for a prayer. Most of the beggars I've seen in the Tibetan villages have been monks, who are supposed to beg as part of their lamaist religion.

After lunch Zhen and I, no common language between us except my forty or fifty word Chinese vocabulary, went to the monastery. We passed a long row of prayer wheels, then walked a street lined with monk residences. Young monks, some not more than seven or eight years old, ran and played and climbed fences, purple robes flying.

This was a giant complex of buildings, and we couldn't figure out where to start. We entered a side room filled with papier mache monsters, the smell so dank we walked right out. Then we tried the temple's main door and were sent to buy tickets several buildings away only to discover we had to wait an hour for the next English-speaking tour.

I'd glimpsed several narrow side streets in the village that I was anxious to explore, and I chose them over the tour. We walked muddy little alleyways that I would have hesitated to enter alone, alleys untouched by cars, though occasionally disturbed by a motorcycle or bike. Children trailed us, sometimes friendly, sometimes not quite friendly, screaming "hello," and insisting on an answer. A young and handsome Tibetan monk, curious about me, walked along with us for awhile. We found a street along the edge of a narrow wadi. On the opposite side of the wadi, the scene was completely rural, people threshing, piling, hauling loads of grain on their backs, someone relaxing on a haystack, all this taking place at the foot of a mountain. I happened to glance upwards and on the very top saw a strange structure built from sticks, banners waving on all sides. Zhen, as fascinated as I was, asked a passerby about it, but couldn't tell me what he'd learned.

I went wild with the camera, snapping the everyday events of life, men playing games on the sidewalk, peddlers dragging carts, cows clomping along a narrow street, a man repairing his bike, his sheep sleeping at his side, reapers, threshers, eaters, walkers, old people, babies, children screaming hello. Zhen began to sense what interested me and pointed out potential subjects, lovely Tibetan women in traditional dress, a construction project. A worker on the ground tossed bricks to the second floor, one at a time, using a shovel as a propellant, and Zhen wanted to be sure I caught a brick in mid-air... Just before we got back to the main street, Zhen peeked into a tiny shop and discovered a man making tofu, pouring soybeans into a grinder where they were mixed with water and came out soy milk.

...Now it's 6:30, I'm getting worried about Eli. He did say he'd finish around two or three. What is there to do in this town after that? I guess we never stop being mothers. Eli didn't pick the easiest job for himself, traveling to remote areas of China to buy things to sell on the other side of the world, dealing with vendors, honest and shady, always surrounded by curious onlookers who watch to see where he hides his money. I wish he'd go into a back room when he pays. That's what makes me nervous. He told me we'd have to be extra-careful, and he's the one who isn't.

Tomorrow we drive back to Lanzhou, another six or seven hours. The next day we begin what may be a 45-hour train trip to Canton. In the meantime I wish Eli would get here. I keep hearing footsteps that aren't his. If he doesn't get here by seven, I'll go tell Zhen who's staying in the room next door.

Well, he made it. At seven. He has no watch so he never knows the time.

A tiny graying Tibetan woman wearing a giant olive green, well-worn coat, her black hair long and stringy and topped by a soft, narrow-brimmed straw hat, shuffles down the street, tripping occasionally on her hem. She passes, then returns moments later carrying some empty grain sacks. I'm waiting in the car while Eli helps Zhen get a good price for a couple of knives to give as gifts. Now they're back, and Eli tells me to hide the knives in my bag in case we're stopped by the police again. They won't bother foreigners or minorities, but the Han Chinese aren't allowed to carry knives.

"Hey, Eli," I'm saying, "Ask Zhen what he found out about the structure on top of the mountain." That's been on my mind since yesterday. And now I'm finding out. It was for the Tibetan dead. The Tibetans cut up the corpse, leave it on the mountain top for the vultures to eat, then grind up the bones and mix them with flour so the vultures will finish them off.

"Ask if Zhen has had a lot of American customers." It turns out we're the first.

"Did he enjoy our walk yesterday."

"It's the longest walk he's ever taken. Before his car, he biked everywhere."

Pigs, cows, donkeys, sheep...uh oh, here's that police checkpoint, and again we're stopped. The first policeman doesn't recognize us, which means he wasn't here two days ago; the second one does and lets us leave.

Eli says, "It'd be nice to take a path in these mountains sometime and follow it for a few days."

"I'd do that."

"You gotta like camping."

"Well, I'm not big on camping, but I'd do it."

"I don't think Dad could walk in the mountains."

"Actually he can. But I don't like ledges."

"That's what all these paths are."

"Then I'm out before I'm even invited..."

Annoying how quickly reality can set in. I hope he's not planning to take Isaiah.

Eli said we should have taken the tour of the Tibetan monasteries yesterday. There are whole expanses of prayer wheels, one going completely around one of the temples. But was it a mistake when I had such a wonderful walk instead?

I'll have to go to some other monastery, maybe in Tibet, though I'm not prepared for the 48-hour bus ride. There's a plane from Chengdu, but China Airlines is one of the world's least safe airlines. It's probably safer than that particular bus ride.

A yak... A biker leading a cow on a leash. ...Bikers crossing without even looking, cart of dead sheep. Pedestrians and bikers ignore us although we're hurtling through...market day in this village, white caps everywhere. Ten thirty, 139 kilometers to go, and no breakfast. Zhen is anxious to get back...Ooh, another biker almost gone. There have been a lot of close calls, for others... Zhen lives with his wife, his mother, and his one-year-old baby...

"Does your wife worry about you when you take trips like this?" Eli asks Zhen.

"Yes."

"Does she get pissed off if you don't call her when you arrive?" Eli asks.

"Yes."

Zhen first met his wife when she was getting off a bus and stepped on his foot with her shoe's high heel. The number of women wearing high heels in China reminds me of America when I was growing up. So does the number of men smoking.

I ask if Zhen notices a numerical imbalance between men and women...whew, a head-on car...Zhen says yes.

"Then what happens when your son grows up?"

Zhen laughs and says he'll look for a wife in America.

Minorities are allowed to have two children, Han Chinese one. If Zhen decides to have another, he loses his government benefits, his retirement, his health care. He has to pay 20,000 yuan a year in taxes for driving a cab. Even if he takes time off, his tax is the same. Zhen toots the horn constantly, uh oh, another town with streets filled with people.

Xinghai and Gansu Provinces have so many Tibetan towns and monasteries because they were once part of Tibet. There are 2.4 million people living in Tibet, yet about 7 million Tibetans live in China.

...As we get nearer to Lanzhou, Eli comments, "They say here that the Muslims are very good at business, like the Jews."

My ears feel the speed, the height, and the constant tooting. The stress of almost killing so many people is getting to me, but not to Zhen and Eli. I can't imagine driving here. Eli says that in Beijing and in several other cities, foreigners can't rent a car unless they rent the driver with it. Where they are allowed to rent, it's by the hour, and prohibitively expensive..."Can you imagine what would happen if a foreigner hit a Chinese?" Eli says.

Zhen likes driving a taxi. His work unit was a sales office, selling machinery... A load of people and one sheep in the back of a tractor truck. Cabbages bigger than basket balls... His job was driving clients around. He's had this car for only three months. Why does Eli ask him a question when he's on the left-hand side and there's a bus coming? Tooooot...

Piles of wheat, corn husks. "We're getting into a Han area...Truckload of potato sacks... We should be back by one..." The area on the right reminds me of the Badlands, on the left is a mountain range...more potatoes... "They must have had a really good crop of potatoes this year," says Eli.

The mountains here are too steep to terrace horizontally, so a lot of fields are almost vertical. "It's hard to imagine how anyone can stand there to plant," says Eli.

"Or how the seeds stay in the soil when it rains," I add.

"The price of furniture has gone up, not a lot of wood. You can't cut down trees anymore." We're going through the furniture market again, back in Lanzhou...This car cost Zhen 170,000 yuan, that's 20,000 dollars, and he paid for the whole thing.

"That's a hell of a lot of money," I say. His wife, his mother, and a group of friends got together to help. He has to pay his friends back, but not his family. No pit stops this time, no food, I'm ready for both.

On the train again...This area is brown, canyons with the tops flattened into fields that are tilled right to the edge. But nothing growing. Grain harvested and stacked, river beds dry. Yesterday it was hard to imagine working the almost vertical fields, and today's horizontal fields are equally forbidding. How can they plant when every little field ends in a lethal drop? And how do they water the fields? Eli said with humans and buckets.

At lunch, as we ate spinach, which in the States has the highest pesticide residues of any vegetable, I wondered if the Chinese had ever heard of organic farming. Eli said, "Give them 75 years. Right now they're struggling just to get enough food."

In yesterday's China Daily, a graph showed the pollution levels in China's major cities, indicating to me that at least air pollution is becoming an issue here. Beijing was the worst, Lanzhou not far behind. We seem to be taking a pollution tour. Vehicle emissions are the major pollutants in Beijing. Coal burning, construction projects, and "dust-raising winds" are the culprits in most cities. I know the use of coal for cooking is one of the worst pollutants world-wide; and in most countries solar ovens could be a feasible alternative, but only, I guess, if diets changed. It would be difficult to sauté vegetables in a solar oven!

When we got to the train station, we checked on the length of this trip. Forty-eight hours. When we boarded, we checked again. Forty-two hours. By the time we get to Canton, we will have spent 110 hours in planes, trains, and automobiles in twelve days.

Before we left Lanzhou, I prepared for this train trip. At 6:30, though it wasn't yet light, I walked a mile to a park where Zhen said people do tai chi. Hundreds of men and women were dancing, all doing the same step, to disco music, and I thought, boy, is this a mass culture. I wandered through the various groups, sword play, Qi Gong, more dancing, people doing their own stretches. I love all this activity in the parks at daybreak. And I marvel that the Chinese take their exercise so seriously. They live in polluted cities, bike without helmets, ride without seat belts, cross major intersections without traffic lights, farm on the edge, but at least as they age and realize their bodies are falling apart, all over China they exercise. Of course they also bicycle, which I consider exercise, cutting in front of cars without looking, pedaling down either the left or right-hand side with buses, trucks, cars, and other bikes coming at them from all directions.

I found two men doing the 24 and joined them, sensing the delight people here show at the sight of a Westerner doing tai chi. When they finished, they placed me between them so I could follow a version of the 24 I didn't know, then we did the 48. A few yards away a large group of men and women who'd been dancing earlier were just about to begin the 24, so I joined them. Afterwards someone made sure I was in the middle in case I needed to follow, and we did that new 24 and the 48. I could have spent the morning going from group to group. But I knew I had a mile to walk before meeting Eli for the breakfast buffet where I could eat what I have at home, muesli, corn flakes, bran, bananas, fruit salad, and yogurt, pleasant change after rice gruel.

Since I knew the words for tea and for eight, before we left Lanzhou, I managed, all by myself, to buy some Eight Treasures Tea to bring home, .. The dense fog outlines trees, ridges, gorges, everything fades into layers of grey.

I'd love to stay in one place instead of whizzing through, but I'm here both to write and to help Eli, or at least give him moral support. He's carrying way over a hundred pounds at this point. I hope he has an iron heart.

...I just did my tai chi in the corridor. There hasn't been any organized exercise on this trip. Going from Beijing to Lanzhou, one of the attendants organized tai chi exercises, so I had a long line of company stretching, bending, and twisting with me....Still foggy, mile after mile of fog, hints of distant trees, I'm living in a Chinese print...

Doing Tai Chi in a group, large or small, in a park in China, is a very special experience. It's different from doing it in Lake Park with a group of Americans. The degree of concentration and the energy are much more intense here, even on my part. And of course it's all mixed in with the exotic, although China seems somewhat less exotic each time I come, except perhaps for the Tibetan villages. It becomes where I am, I've been here before, it's fascinating, but so is life everywhere. Eli feels this much more strongly than I do after all the time he's spent here. It's simply a normal part of his life.

11:40, twenty minutes to dehydrated noodle soup rehydrated with boiling hot water from one of the giant thermoses under our little table. At first I didn't want to pour from them, sure I'd spill and burn. But then I got used to them, a normal part of life, and realized that pouring from them is no big deal. Actually I'm not hungry. Eating simply breaks up the day.

Before catching the train at 4 PM, our project for yesterday was to find a book in English for Eli. The hotel clerks suggested two stores. At the first, the only book was Lolita, first in English, then in Chinese. The second store had several floors of books. The English section had Hardy, Conrad, Austen, Twain, Agatha Christi, and Mario Puzo, and movie scripts with Chinese and English side by side. The book search gave us an excuse to walk several miles, the perfect activity before a two-day train ride. I'm sipping Eight Treasures, refilling time after time. By now it's slightly favored water, good way to make myself drink liquid, also forces me to know the WC intimately. This one is very clean and well-designed, raised where the feet go, handle on the wall in front to hold onto when squatting, a shield in front for those who over-squirt, hole shaped so that anything that goes in hits the tracks immediately, good way to lose a passport. A slight breeze wafts upward, which must be difficult in winter.

We're in a station, hundreds of people running, carrying heavy bags, sacks, babies. There are so many about to board, I'll bet this is where we'll get roommates. Eli says no. If they're running, they're not in soft bed, they're in hard seat, and they want to be sure to sit. The government sells as many tickets as there are people to buy them. "Now some people are coming back this way," I say. "Maybe they couldn't get seats."

"Couldn't get seats, hah," says Eli, "Maybe they couldn't fit into the train." Now more people are streaming past towards the exit. They must be people who just got off. Took them a long time. "Sometimes people pack in so quickly, passengers can't get out," Eli tells me.

We still have fifteen hours till we reach Canton. If we go through flooded areas, it'll be in the dark. Now that I'm here, I haven't heard too much about floods. But where would I? I saw that page in the China Daily devoted to the heroes of the Mongolian floods, that's about all. In response to my questions, Ling Tao said most of the houses in her hometown in Inner Mongolia were destroyed, and the army came in and rebuilt everything.

Television is omnipresent now. There's even an English-language newscast every evening, the Chinese version of world news. I haven't managed to find English language news about China, nor have I found CNN. The other English programs I have seen were sports, cooking, and inane interviews patterned after American talk shows. On Chinese channels I found one that specializes in music videos and another that seems devoted to the Communist Party. I'm looking forward to the International Herald Tribune in Canton.

It's night now, our lights are out, so I can see outside more clearly than I can see my writing pad, one of the rare moments in which I'm the unobserved observer. We're in a station, I have no idea where except that we're about fourteen hours from Canton. A train is passing us, car after car of hard bed, people standing in corridors, seated on beds or suspended between them, looking out the windows of the accelerating train, none seeing me. As we entered this station, cruising through the dark, a giant illuminated pagoda suddenly appeared, then it was dark again, as if the pagoda had been a dream emerging on a hilltop.

We got off the train into Canton's same old nightmare station, Eli squeezing through crowds with a two-hundred pound backpack, rolling a heavy suitcase behind him, grunting every few minutes, "Boy, is this heavy."

We went to the White Swan Hotel, changed clothes, went out to buy train tickets for tomorrow night, ate for the first time today, and now here we are, again in a wholesale market. A lot of peddlers were forced to move from the marketplace into a three-story building, and Eli can't find the people he dealt with before. Each seller has his own little space. I watch them talk to Eli, eye him intently, most of them more or less his age, all of them anxious to make a major sale. Now Eli is showing them photographs of Isaiah, and a small crowd gathers. He says something, and they all laugh. I don't know what's going on; I just sit here on a stool a foot high and write. Now they're all looking at me, guessing my age. I think they guess low if they decide my hair is blond, high if they decide it's white. I can see intricate carvings at the level of my eyes, probably ivory, obtained in exchange for the life of some poor elephant. It's illegal at home; unfortunately not illegal here.

Now I'm in the outdoor market. A woman sits on the ground behind an array of morbid objects: a small black skeleton made of wood, a large claw made of whatever animal it once was, a small paw, a furry section of scalp with horns. She's young and lovely, hoop earrings, print jacket, several necklaces dangling round her neck. I want to photograph her. Damn, she waggles her finger at me.

...Now I'm sitting about a block from the hotel, outside a store while Eli visits the owners, whom he knew when he lived in Canton. I notice a stroller, possibly the first I've seen this trip, then I see the mother, American. I look at the baby. Chinese. Now another American, with Chinese twins in a twin stroller... Here's an American with a front carrier, holding onto her new baby's toes...There's a sign in a nearby store: Special stuffs for adoptive parents.

The Americans stare in wonder at their newly-adopted babies, feel their feet, kiss their foreheads, caress them, feed them. Three or four adoption groups are staying at the White Swan Hotel, which is one block from the American Consulate. The Holt Agency brought over seventeen couples, (actually one woman is a single parent) from several cities, Chicago, Madison, Los Angeles, Eugene. None of those we met had ever before been to China. They first spent a week in Nanking where the Mother's Love Orphanage has a foster home program for abandoned children, so they know their babies were in foster care before adoption.

The whole process, including the trip to China, cost between thirteen and twenty thousand dollars and took about a year. The babies are all over a year old. Adoptive parents must be over 35; the combined age of a couple can't exceed one hundred years. It's also preferable that the adoptive couple not have other children. The Holt Agency held orientation sessions, helped the parents to understand where their children came from, and took them to their child's native village. The new parents were anxious to immerse their children in Chinese culture.

I can't imagine what it must be like for someone never having been to China to suddenly find himself in this strange land and the parent of a strange baby. What could it be like for the babies, hearing Chinese for over a year, then suddenly swooped up by strangers speaking strange words?

We also met a couple flown in by another agency. The rest of their group didn't show up, so their agency's representative devoted herself to them full time, taking care of the baby. In fact, they wanted to hire her permanently. I asked the husband if they'd take their daughter back to China sometime so she could get to know her roots, and he said, "Never, I'm never coming back to this country. I'm taking plenty of videotape so she can see what the country is like. If she wants to go to China, I'll take her to Chinatown." Eli told him a lot of kids like that end up in Taiwan or China very confused. They look the part but can't speak a word of Chinese. We were seated at adjacent tables in the White Swan's restaurant, and I suddenly realized that I had no idea of what I was eating, something I'd assumed was a very small chicken.

Eli said, "Looks like pigeon."

The adoptive father said, "I hate the way the Chinese serve chickens and eels, with their bones still in."

His wife had been silent the whole time. I commented to her that the whole experience must be pretty traumatic, and she replied, "Oh, it is! We've been preparing for this for two years, but when you finally get here, you're totally unprepared."

"Do you know very much about your baby?"

"She was abandoned when she was eight months old with a note just giving her name and age, and she's been living in the orphanage over a year."

"Did you see a lot of photos of her ahead of time?"

"Just one little snapshot," said the mother.

The father took it out of his wallet, "This is it. After all that time, were we going to say no?"

"Well, you're lucky, you got a very beautiful child."

"Oh, yes, she's very beautiful," said the glowing mother.

"Should I buy it to open it up? Is it worth it?" Eli asks me. He's been arguing with a vendor about whether or not some bracelets are turquoise. The vendor takes a hammer, conks it, and we see the bracelet is stone, turquoise colored all the way through.

The day is heavy, though not in the 90's, thank goodness. It's 1:15, we leave soon again, on a 15-hour trip.

We have only a few minutes left but Eli's negotiating. He picks out seven carvings, the woman asks a ridiculous price, I keep showing Eli my watch, her price is cut in half, it's still too high.

We're in a cab, lively section of Canton, mini-skirts and high heels, shorts, tight pants, long dresses, blue jeans, not a single Mao suit. There's an incredible amount of housing construction. The part of China our driver comes from was flooded. I ask about homelessness, and he said the government hasn't finished rebuilding. We're trying to squeeze in front of a bus, very tight traffic, cabs, motorcycles, cyclists wearing helmets.

It's like a grab bag. We peer into our soft bed compartment and odds are two fresh faces will already be there, and we'll spend between fifteen and forty hours with them in very close quarters. This time we found a forty-six year-old businessman who deals in electrical supplies escorting his eighteen year-old son back to police school outside of Guilin. The father is round-faced, handsome, charming; the son, extremely shy, has never before spoken to an American. Eli shows them today's purchases and gives the son a jade carving. Eli and I had the upper berths, but when the father found out I'm sixty-one, he insisted I take his son's bed. "I'm glad I gave him the jade," Eli is saying, "It was very nice of them to give you the lower. "

I tell Eli to thank him again. The man replies, "In China we respect our elders." Funny, I don't think of myself as an elder.

...Our roommate smokes three packs a day (not in our compartment) at 35 yuan a pack (about four dollars), so he spends over twelve dollars a day on cigarettes. He makes US$120,000 a year, spends $3600 a month on living expenses, and has five children. The son he's traveling with is the middle child, born in 1980, when the one-child family law went into effect. They didn't start cracking down until 1985.

Lying here tonight, listening to Eli "shoot the fat about cars and roads and sports, nothing worth translating," I compared Eli's intonation to that of our roommate. Eli sounded amazingly Chinese. When someone speaks another language well, he takes on another personality. I notice it when my sister speaks Spanish; Mexicans ask her what part of Mexico she's from. And I notice it when Eli speaks Chinese, though I doubt too many people think he's from China. I thought of Eli's talent for mime. He used to do wonderful take-offs on all of us. That ability has stood him in good stead, even though he never became an actor.

So here I have a son who sounds Chinese, but doesn't look it, and that last couple has a daughter who looks Chinese but may never sound it. Still, it's moving to see all these people with their Chinese babies. I've been holding babies a lot the past six and a half months, so I relate in a physical sense to their experience. Of course I'm grateful that at this stage of life, I'm only a part time holder of babies.

Out of the train, into a cab, no food since 3:30 yesterday. When Adolph sees how much weight I've lost, he'll want to come to China. This taxi is only two years old, made by a German-Chinese corporation. "Whew," says Eli, up front as usual, "this guy drives eighteen hours a day, seven days a week." I hope we're not his eighteenth hour passengers.

...There's a helmet law for motorcyclists here, too. People don't dare disobey, fines are steep...It's rush hour, woman in miniskirt pedaling along, another in pedal-pushers, that makes sense. Rush hour consists mainly of bikes, then motorcycles, next in number, buses.

Eli wants me to take out the photos of Isaiah, and I reply, "Not while he's driving." It's normally a one-hour car trip from Guilin to Yangshuo, but they're repaving the roads. I ask Eli if the driver has said anything interesting.

"He said America has a lot of racism, and I said yes. I asked him if China has any, and he said no. I asked about racism against Chinese minorities, and he said some people don't like the Tibetans because they want to become separate."

...He's already paid off his car, 40,000 yuan down payment, the 80,000 yuan balance paid off at 5000 a month. His 400,000 yuan house is paid off, too. Business is poor right now. He's got a six-month old son; that's why he's working so hard, saving for the son's future, his education, his marriage, his business.

...His wife works in a bank, and his mother, with his father's help, takes care of the baby. His parents, and his wife's, live next door, well, not exactly next door, on different floors of his four-story house, all eight of them, including his younger sister. He and his wife support them, well, his parents have retirement money coming in, and his sister works. She's seventeen and very pretty, he's twenty-five. He married early. He thought I was forty-five or fifty. Eli told him I do tai chi and Qi Gong. The driver said I'm like Bruce Lee.

"Why is business bad for him now?" I ask.

"He says there's a recession, almost a depression. When he first started, he earned 20,000 yuan a month, and now it's down to 6000...The Taiwanese used to come here and he could make a hundred bucks American on this little trip which we're paying less than $25 for, but there's a recession in Taiwan."

"Does he think China's recession will get better or worse?"

"He's very pessimistic, too much corruption, people are greedy."

It's almost 9 AM, I'm hungry. Eli says he's concentrating on business and food is the last thing on his mind. Anyway I feel better on an empty stomach.... They're drying out some sort of medicinal herb on a large patch of cement. Lots of roadwork here. I wonder how many thousands of miles we've covered in our first sixteen days.

...While I was doing tai chi in the park next to the White Swan, a woman thrust her face within inches of mine an, speaking English, tried to get me to go to her tai chi master. I kept right on doing the form, amazed that she didn't respect my right to do tai chi in peace...

Afterwards I followed a sound reminiscent of a howling wolf with human undertones and found a group doing Qi Gong. As always someone adjusted my hands and demonstrated the proper stance and movements. Then I found another Qi Gong group with another eerie-sounding tape.

When I finally was ready to leave, the English-speaking woman escorted me out of the park, inventing as many questions as possible so she could practice her English. I took a close look at her tai chi sword The blade was blunt, and the sword short, but it telescoped to a normal size. Seeing it was a reminder that, though I rarely think of it that way, tai chi is a martial art.

Later. Everyone knows Eli in this village. We're sitting at a table in the middle of a shop and eating a sweet, grapefruit-like fruit, throwing rind and seeds on the floor, and the vendor is telling Eli that the Tibetan village we just stayed in has a lot of criminals. It's a good place to escape to, it's so remote. They can disappear into the mountains. He wouldn't want to go there; it's too dangerous. They rob the busses and the cars on the roads. More drugs are there than anywhere else in China.

Eli replies that there's risk in everything you do. If he wants to get some good stuff, he has to go there.

Before we came, Eli had bought a gift for a vendor's daughter who has sickle cell anemia and probably won't survive. Since she loves art, Eli chose a set of drawing pens. We just saw the vendor, Kai. His daughter is much worse. Eli wishes he'd brought more for her.

"You can still give her the pens."

"It's useless...I usually buy a lot from Kai, but now I don't know."

"He still has to make a living." We went to his shop. It was closed.

"I'm going to give Kai a bonus," said Eli.

...Kai's shop is finally open, and the mother told us the girl is doing somewhat better today, but her stomach is distended, and the end is near.

Now we're in another shop. Someone tries to sell Eli plastic made to look like bone. Eli insists it's plastic. Finally the vendor admits he's right.

...Back in Kai's shop. Eli gave him a hefty cash gift, though Kai doesn't know it yet; he hasn't looked into the little red envelope. His daughter, retaining fluids, is very bloated, and her organs are closing down. She'll be twelve in eight days, if she makes it.

Someone else comes in; he and Kai are speaking the local dialect, so Eli can't understand. Kai's brother, owner of the adjacent shop, stops by, cigarette hanging out of mouth. He tells Eli there's no way for him to stop smoking. He stopped drinking, started eating fruit and seeds, nothing helps.

A German woman wanders in. Eli tells her Kai has fair prices, and she buys something.

"Kai has been using Western medicine to treat his daughter," Eli tells me, "and it's so expensive most of his money is gone."

We just visited a house Kai is renovating, so he must still have some money left. He bought a one-story house and made it into four stories. As we went up each flight, Eli warned me to be careful, no railings. I'd already noticed, but went all the way up to a spectacular view of roof-tops and limestone karsts. The house, still under construction with stones and bricks, was empty, except for chestnuts set out on the floor to dry, and a motorcycle. As we looked at each uninhabited room, I wondered if Kai was thinking that his older daughter would probably never live here.

...We're in the shop of the first vendor, waiting for his wife to finish making dinner. The vendor says that Kai should have taken his daughter to the hospital sooner...

When Eli asked the wife to guess my age, she said seventy. He told her I'm only sixty-one, and she replied that I'm in good shape for sixty-one.

Okay, I thought, I'm going to see once and for all whether or not it's my hair. "Ask why she thinks I'm seventy, then says I'm in good shape although she discovers I'm much younger than that."

He did, and she told him it's because I have white hair.

Now the vendor tells Eli I must be in very good shape to travel around with him, that people my age in China don't "travel like that."

I don't know what they're saying at the moment, and Eli doesn't translate since they're "talking business." Someone else just sat down with us, no more business talk. Like a lot of vendors, our host and his family live in the back of his shop. In fact as we walked down the street before supper, I noticed that every single shop had a television turned on, and in many the whole family was watching.

It's hot in here, even though the front is completely open.

I ask our host if he rents from the government. No, this building has been his family home for eighty years.

"Didn't the Communists take over people's homes when they came into power?"

The vendor says only the upper class homes. They left the lower class alone. The man who just came in was upper class. They took his family's home and never gave it back.

"What do you do for a living?" I ask.

"Not much. I used to be an architect, but there's not a lot of work right now." He lives off his savings. He's got two kids in their 20's, one of them in college, and he supports them, 400 yuan a month. His work unit is useless, in fact a lot of them are dispersing now. He has a house that he built himself. The original house was much larger. The Japanese took it over during World War II, then the Communists.

Today is Saturday, and it's strange to think that this Friday I'll be rehearsing with Marie and Tony in Milwaukee.

Late to bed, late to rise, so when I arrived at the nearby park this morning, tai chi practitioners had already done the forms and were up to swordplay. I didn't mind; it was special to eat with the vendor's family. Eli said most people in the village don't want to be associated with foreigners, or everyone will think they have a lot of money.

The vendor, his wife, his son, Eli, and I sat on six-inch-high stools and ate at a low, round table from which we could see if anyone came into the shop. If someone did, the wife would quickly get up, put her bowl in a cabinet, and go to wait on him, closing the curtain so no one would see us eating in the kitchen-dining-living-room. She'd prepared several kinds of mushrooms cooked in pork broth, ground pork balls in tofu skins, fish from the Li River, spinach in fish broth, and pickled string beans. Reaching with our chopsticks, we ate out of the serving bowls and spit the fish bones onto the stone floor. Since we had no plates to fill, I could have inconspicuously eaten a small amount; too bad I liked the food. Once I'd finished, they offered me rice, and I refused. No matter how many times I said it was a great meal, they insisted that if I wouldn't eat the rice, I didn't like the kind of food they'd prepared. "I guess you'd better have some rice," said Eli. Still later, the wife brought out fruit, and again they insisted that if I wouldn't eat the fruit, I didn't like their food. This time, I just couldn't. Anyway by then I was standing up. After sitting all day on six-inch stools, my butt bones were sore and my hip joints felt as if there were needles stuck into them.

We ranged all over the conversational map at dinner.

Health insurance? People in business for themselves aren't covered by the government's health-care system. Buying insurance isn't worthwhile; a basic check-up costs only 10 yuan. Both doctors and lawyers work for the government, which means their earning potential is modest. Doctors don't get rich, nor do they study as long as American doctors, just five years after high school. Their daughter has finished three years towards her degree.

Again our host criticized Kai, this time saying he should have used traditional, not Western, medicine. Traditional is good when you're sick, Western good when you're healthy. Traditional is a slow process, Western a quick fix. Perhaps he made his comments in the hope that knowing what someone else did wrong can help him to avoid the same misfortune.

What does their son do? He's part of a work unit that sells real estate, except there's no real estate to sell. He makes 300 yuan a month for doing almost nothing, and he helps his parents in the store.

Welfare? There is none. You'd better have a family if you're unemployed.

Retirement benefits? Eighty to ninety-five percent of salary. But if you have your own business, you don't get anything.

Are there more boys than girls in China? They thought it would be very hard to abandon little girls, since you can't hide the birth of a child.

Did the son serve in the army? There's no draft, and you have to be very fit to get in at all.

How large is the army? The government doesn't give out that kind of information.