by Suzanne Freedman, 1958

I had unhesitatingly accepted Djemel's invitation to visit him in Douz, a little village in the Sahara. My mind, however, was not at ease, for even Tunisian friends had told me I was very courageous to go so far, and to go all alone. But I couldn't imagine visiting Tunisia and not going to the desert.

So on Monday night I found myself in a truck, bouncing over the sand road between Kebili and Douz. Djemel, who'd met me at the train, warned me to prepare myself for no electricity, no heat (Sahara nights are cold), and no running water. He didn't mention that I'd be living in a school with five schoolmasters. I discovered my situation quickly enough, for when we sat down to eat (two minutes after arriving), I was the only female. Even the cook was a man.

After supper, guests started coming to see the American in Douz, or rather (just as much a novelty) the unveiled female in Douz. When our number had swelled to twelve men and woman (me) sitting on wooden chairs and benches in the living room and drinking strong tea from little glasses, Djemel presented everybody to me and me to everybody. One of the men gave me the skin of a gazelle, then we spent the evening talking, singing (Arab songs by them and Calypso by me), and laughing. Two of the men did the danse du ventre while the rest of us drummed on the table and chairs and chanted oriental songs.

When I got tired, the men carried a bed into the living room, made it, and lent me a pair of pajamas. Then they each shook my hand and filed out of the room. Djemel and Khali gave me a lantern and a flashlight and closed the doors. They barricaded one door. I later found out it was only because the door wouldn't stay closed.

The following morning we had to visit the délégué (President Bourguiba's representative). Djemel and I went to the town hall, which looked just like the school, the shops, and every other building in the center of the village.

The délégué didn't speak French; in the South even many educated Tunisians only speak Arabic. With Djemel translating, the délégué first asked what I would like to drink. No matter whom you visit in Tunisia, you must have something to drink or eat. As we sipped tea, the délégué outlined government projects in the region, like dividing up a tract of arable land among 217 families, one hectare per family for growing date palms, fruit trees, and vegetables. The government also introduced a new breed of sheep and will lend families with no source of income money to buy them .

Since Tunisia's independence the number of classes (fifty students per class) in Douz has increased from three to nine, and some girls now go to school. Although federal and local governments are building more schools, right now all education in the region is still primary. Gabes, a coastal city about 200 kilometers away, has two secondary schools.

The Ministry of Public Health waged a successful campaign against trachoma, an eye disease prevalent in Southern Tunisia, thanks to an intense information program and to the sale of a pomade for 25 francs at groceries and pharmacies. Douz has no pharmacies, and until the government opened one in Kebili (30 kilometers away) last year, the nearest store for medical supplies was in Gabes. The Ministry sent four nurses here and asked in return for four girls from the region to study nursing in Tunis. It is building infirmaries, and has provided an ambulance with equipment for operations in the region of Kebili, Douz, and Matmata.

Afterwards, on the way to the school where Djemel teaches (not the one we were living in), we met, believe it or not, another American! June, the only American I met during my month in Tunisia, was traveling with Paul, a Dutchman who makes watches on top of a mountain in Switzerland. When we arrived at the school, the children came running across the sand to meet us. There were five or six girls, some with tattooed faces, all of them wearing earrings. Many of the boys had shaved heads. The school building was modern, opened last October. Its two classrooms are used for three classes. Djemel taught both inside the classroom and outside on the sand. The children were studying Arabic, and when a child consistently wrote or pronounced a word incorrectly, Djemel pulled his earlobe a couple of times.

I watched for about an hour and a half , then visited the school director's wife, who lived in a flat over the classrooms. Unlike the other women of Douz, she wore bright colors rather than black. I soon found out why: she was from Gabes. She was 17 years old, had been living in Douz four months, and was the only unveiled, and the only educated, woman in the village. Sometimes the local women visit her. They are very friendly, but uneducated and tradition-bound, and she doesn't know what to talk to them about. After drinking a glass of tea and promising to introduce her to June the following day, I went with June and Paul to photograph a camel delivering firewood to their trailer. I took pictures with my Kodak box camera. In fact in the next 48 hours I used up five rolls of film (every roll of 620 film in the village of Douz).

After lunch the chief of the National Guard stationed in Douz took June, Khali, Djemel, and me to a fort the French built in 1885 and evacuated in 1957. Barbed-wire fences surrounded the fort, and any Tunisians who entered the enclosed area during the French occupation were shot. The French would lower them into a well to muffle the screams and shots. Before leaving the fort, the French troops had broken the floors, walls, stairs, windows, pulled out the sinks and telephones, even mutilated the trees in the courtyard. About the only thing they left in recognizable condition was a canon. The fort is too badly damaged to use, and the government can't afford to restore it.

I asked how Tunisians feel about the French.

"The Tunisians love the French. " The National Guard chief smiled and said we are all brothers, the Americans, the French, the Tunisians, everybody. "On laisse les gouvernements, et les civils sont tous d'accord." He seemed sincere. As a matter of fact, throughout the country I found Tunisians resent the actions of the French colonists, soldiers, and government, but they don't seem to hate the French in general.

When Djemel and Khali went to their respective schools, June and I had tea at the chief's office. He took us home to meet his wife, proud that she no longer wears her veil when they have company. She, however, was very shy and acted as if she were still wearing one. Before we left, we had to drink coffee and eat fresh honey and camel and goat butter combined with God knows what else. And I had to try on the white veil of a Tunisian city-woman.

That evening, Djemel, June, and I strolled along the outskirts of the village. The houses, further apart than those in the center, were one-room boxes made of sand bricks and separated by dunes higher than the houses themselves. Women in black sat outside and prepared dinner over little fires. The sun was setting behind the palm trees. The sand houses reflected violets, pinks, and blues, and a star appeared, adding a touch of light to the quickly darkening sky. I climbed to the top of a dune. A goat bleated as it scampered by. A Bedouin drove his herd of sheep through the shadows a few yards away. On all sides the pastel sky framed black palms; the dunes and houses made long dark shadows in the sand. I wanted to stand there for the rest of my life.

But it was getting cold and dark, time to leave. A group of men were sitting on the ground, chanting evening prayers that sounded like poetry. I listened until Djemel and June pointed out that it would be difficult to find our way back in the dark. Even in the light, we soon had no idea where we were; all the houses and dunes looked the same. Finally someone guided us to the school, where the chief and a Guardsman were waiting to check my passport. The schoolmasters invited them and June to stay for dinner and sent someone to get Paul. After dinner two poets who had recently won the Poets' Prize of President Bourguiba stopped by. We all sat in a circle, and they recited their poetry in Arabic. I couldn't understand, but the music of the words and the reactions of the men were enough to keep June and me enchanted for hours. The gentle yet dramatic manner in which the poets expressed themselves would have made them poets had they never written a verse. One of them recited a poem about the emancipation of women. After every line at least one of the men would say something in agreement, seeming to be as involved as the poet. A few poems were amusing, punctuated by frequent grunts of laughter. Too bad the schoolmasters couldn't translate!

After the guests left, Djemel called me out to the back yard. "Listen carefully, some women are singing at a wedding." I didn't want to listen, I wanted to go. The voices were far away and the town dark. Since weddings last three nights, we decided to go the following night.

The next morning June and I walked in the oasis of date palms. The land between the palms was divided into tiny plots for vegetables and workers turned the soil with short-handled hoes.

Then we visited the two classes that are taught in the school I was living in. The class of first year students (six and seven year olds) had five or six girls; the other class, about two years older, had only one girl.

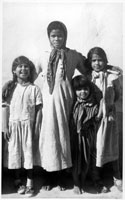

I took June to visit the director's wife in the afternoon. We drank tea and discussed the situation of Tunisian women in general, Douzian women in particular, and the Gabesian woman in Douz. The women of Douz go out only to wash clothes at the artesian well and to bring home water, which they carry on their backs in heavy clay jugs. They don't go shopping, but instead send their husbands to the market. They wear black veils and skirts, silver hoop earrings, and silver necklaces; and their faces are tattooed.

The director's wife dressed me in one of her own outfits, that of a Gabesian woman, and the three of us went out to visit a family June knew. The women ran over to meet us. After each woman shook hands with one of us, she kissed her own hand; that meant that she had affection for the person whose had she'd shaken. The women were amused that the director's wife, who was dressed in Western clothes, was a Tunisian, whereas I, dressed in Tunisian clothes, was an American. They made us sit down on the blanket with them and their babies, brought us branches of dates, and began to prepare tea for us. We could, however, only stay a few minutes because we had an appointment to take a walk in the desert with the director. They gave us the rest of the dates, then we shook each others' hands and kissed our own hands.

The director was waiting, and the four of us set out to watch another desert sunset, keeping sight of the telephone poles (there's a telephone in the post office) so we wouldn't get lost again. When we were some distance from the center, the director commented that any man in Douz could find us by following our footprints, despite the fact that there were many other similar footprints in the sand. The Arabs of the desert can even tell what kind of a burden a camel is carrying by looking at its tracks (I'll admit I'm dubious). There's practically no crime in Douz as there's no way for a criminal to hide his prints (also there's hardly anything to steal). If someone commits a crime, he's caught immediately.

I wanted to see the inside of a house. The director couldn't enter because he's a man, but he said he'd wait for us if we wanted to visit someone. We walked towards a group of women preparing dinner outside. They came to meet us, shook and kissed hands, and, after asking where we were from and feeling our hair and clothes, invited us in. It was a one-room house with mats on the ground for sleeping, no other furniture, and very few possessions. Two of the women, their husband, and one child lived there. I wanted to question the women about their polygamous situation, but the director's wife was tired, and she was the only woman in Douz who spoke both French and Arabic. Before we left, the women insisted that we eat some dates.

As we walked the director and I discussed the problems of a schoolmaster in a village like Douz. He almost never meets the mothers. If it's necessary to discuss a problem with the parents, he can sometimes find the father in the marketplace. Since the parents are uneducated, they are often unable to help. A mother who doesn't know how to read, has no way of knowing whether or not her child is actually studying, and perhaps doesn't care. Very few families are willing to send their girls to school. Often the schoolmasters have to take the children to the well to bathe them, or they would never be bathed.

We had passed the boundaries of Douz. A bespectacled school master who lived in Douz and taught in near-by Galaa jogged by on his burro, heading home from school, which reminded us that it was time to turn back because the délégué had invited all the schoolmasters and me to have tea in his office at 6 o'clock.

Again we sat in the office and sipped tea. I told the délégué about my day and asked him about polygamy. Although it's now illegal, the families that were polygamous when the law was passed remain polygamous. He didn't know the exact figure for Douz, but estimated that thirty percent of families are polygamous.

I asked about his job. As the President's representative, he has a lot of power. He's in charge of all the governmental institutions in Douz: the schools, the post office, the National Guard, and the infirmary. He acts as judge for minor disputes, and a judge comes from Kebili once a week for more important cases, dealing with financial problems, or land ownership.

After supper, when the village was black during the interval between sunset and moonrise, the schoolmasters, the cook, and I, with the help of a flashlight, found the wedding, which was taking place outside. The only light permitted was a small fire which was the sole source of heat. About fifty women veiled in black sat on the ground near the fire; the men sat in a group a few yards away. The bride was in the house; the groom was somewhere among the men.

The man in charge spread a blanket in the sand for us, then brought us tea. I asked if I could speak with the bride, and he said to come the next afternoon as she was surrounded by women that evening.

Two old men stood between the groups of men and of women and sang in a monotone a dialogue to the bride. Djemel and Khali, who aren't from Douz, couldn't understand the dialect and had to get someone to translate for them. After singing for about fifteen minutes, the men got tired and sat down. Some women chanted awhile. Then the men got up again and sang about the Tunisian War for Independence: where the men in the region camped, what they ate, how they fought, who their generals were. Then two other men sang the story of Aouina. The schoolmasters told me that during the Second World War, when the Germans occupied part of the South, twenty men from the section of Douz called Aouina hated French colonialism so much that they decided to work for the Germans. When the French came and occupied the fort in 1943, the twenty Tunisians fled into the desert. The French soldiers took their wives as hostages. One night the twenty men returned, surprised the four hundred French soldiers in the fort, killed about two hundred of them, and saved their wives. Only two of the Tunisians were killed. As a result of this raid, the French general charged the four hundred families living in Aouina a fine of 200,000 francs a week (420 francs to a dollar). The families were poor and had to sell all their possessions in order to pay. The payments continued until 1947, when the people rebelled and the general lifted the fine.

A French author, M. Montety, who has lived in Tunisia for thirty years, told me part of the story somewhat differently. He said that when the men heard their wives were hostages, they sent a boy to the fort to tell the French soldiers that knew where the rebels were hiding. All the soldiers left the fort to go with the boy. Then the rebels, who were hiding near the fort, entered, killed the four French soldiers who remained as guards, and rescued their wives.

When the men finished their song about the heroes of Aouina, they sang about a beautiful girl named Fatma, described everything about her, even the tattoos on her forehead and chin. In the middle of the song, about fifteen men got up and walked out. Djemel told me that the groom was probably among them. At the end of the song, we returned to the school, where Djemel told June and me the story of the Tunisian revolution and we all sang and belly-danced.

My last day in Douz was market day. The animal section was crowded with men buying and selling camels, sheep, and goats; the main marketplace was crowded with men buying and selling bread, eggs, sacks, shoes, clothing, freshly-sheared wool, quack medicines; the food section was crowded with men buying and selling wheat, dates, fruits, vegetables, meat (the heads of animals were left on the ground), and hens.

When we left the market, we met the National Guard chief, who had a rarity with him: a station-wagon which belonged to the village's new infirmary (there are three cars, two pick-up trucks, the station-wagon, and a bus in Douz). The chief drove us to Galaa, a village about three kilometers from Douz. June and I decided to visit another home, although this time we had no interpreter. We walked towards a group of women. They greeted us warmly, shaking our hands and kissing their own hands. We managed to make them understand that we're unmarried Americans; and we managed to learn from them which women were the mothers of which girls. They invited us into their houses. One house had a double-bed, but in the other house the family slept on straw mats. On the walls were photographs of President Bourguiba, of the President of Morocco, of Egypt's Nasser, and of male relatives; and there were picture postcards of New York, Paris, and London. In one house there was a clothes-line on which freshly-sheared wool was drying. The women gave us eggs to take with us.

After lunch in Douz, June, the director's wife, and I went to see the bride. The house was crowded with women who had come to dress her for the final ceremony, the camel ride. Hands pushed at us, shoved us through the crowd of women to a dark corner where the bride waited to be dressed. She didn't want to talk to me and tried to hide her face. Someone made her sit down on a mat. Then, with the director's wife translating in very poor French, I asked questions, some of which were partly answered (the rest remained unanswered).

She was twenty years old and was very frightened because she had never met her husband. She had seen him in the distance twice. Since he was her cousin, she had heard a lot about him from the rest of her family. Although she was afraid, she was glad she was marrying him, for everyone had praised him.

Once again we were pushed through a crowd of women; this time ending up outside. The brother of the groom was standing with the wedding camel a few yards from the house. On top of the camel was a wooden framework covered with a blanket. The bride was to ride under the blanket. Skin bags filled with the bride's clothes and with household utensils were attached to the sides of the camel.

The women formed a tight circle around the bride, covered their heads with a large white piece of cloth, and brought her outside. There, completely hidden from everyone except those who were working on her, the bride was covered with jewelry and her hair was combed. The women argued over what should go where, and how her hair should be arranged. With everyone tugging at her, with no source of air thanks to the crowd around her and the veil over the crowd, and with so many fears about the coming evening, the bride managed to remain conscious surprisingly well. I do think she was crying, and she seemed on the verge of collapse.

Finally the women finished preparing her and urged her to remove her veil so I could photograph her. She refused, and they began to force her; I told them I wouldn't take her picture if she didn't want me to.

Surrounded and veiled, the bride was led to the camel and helped onto the saddle. The blanket was tied firmly in place and the camel rose. The camel, followed by hordes of singing children, carried its burden around the town. We followed as far as the school, for it was almost time for the bus to leave for Kebili, and Djemel and I planned to be on that bus.

When it was time for the bus to leave, Djemel said that first I must say good-bye to the délégué. We entered his office, and of course had to drink something. We drank tea and talked, while the bus, overloaded with men going home from the market, waited for us at the door for fifteen minutes.

On the bus Djemel gave me a wallet made by a craftsman of the Sahara. He said that when I return he might not be there, but there will always be another Djemel and another group of schoolmasters to entertain me or my friends.

[Rosenblatt Gallery] [Suzanne] [Travel] [Tunisia 1958 home]

Copyright © 2003-4 Suzanne Rosenblatt. All rights reserved.

(

No pathinfo

hits since 26 March 2004)