A Dutch couple we met rented bikes to visit a mountain in the countryside about fifteen kilometers outside of Xian. It was the first time they felt as if they were out of the tourist corridor. We decided to do the same thing.

Yesterday was our most wonderful day in China. Nanwutai was the name of the mountain our Dutch friends had visited. They'd bathed in a mountain stream and stopped at Buddhist temples as they climbed. We decided to rent bikes, spend a night in the temple at the foot of Nanwutai, climb the mountain, return to Xian, then take the train to Chengdu as soon as possible.

But the weather forecast was hot, 104 degrees. We thought it would be wiser to take a bus, get off at the last stop, and walk the rest of the way, perhaps 7 or 8 kilometers. Our friends had said to keep going straight; we had our destination written in Chinese on a slip of paper, just in case.

We left everything in the People's Hotel and carried only our cameras and two straw baskets containing toothbrushes, bathing suits for the mountain stream, five flasks of water, and toilet paper. When we got off the bus at the end of the line, we figured we were half-way to Nanwutai, and, judging from the stares, that we were off the tourist track.

Within a half mile of the bus stop we came to a fork, so much for going straight. I showed our slip of paper to a man sitting on a fence, and he directed us to the right. The poplars lining the road offered a little shade as we passed tiny rice paddies and corn fields. It seemed crazy to be walking all those kilometers when it was over 100 degrees. Its hard to breathe in such heat. Still we loved it.

Whenever we saw a peddler, we'd buy the little banana ices that have become our main beverage in China. We've been consuming them for almost three weeks now. They cost less that two cents and are available on almost every city block.

After a kilometer or so, we showed our slip of paper to a passing cyclist, just to make sure we had taken the right fork. She indicated we hadn't, then found someone else to discuss it with. They decided we could reach Nanwutai on the route we were taking.

Adolph's feet were already killing him, and my broken toe ached. There was bicycle traffic, an occasional truck, at one point a bus sped past.

"Ni hao," we'd greet the villagers, How are you? They'd look at us as if we were aliens. "Duo shao?" we asked the boys selling watermelon, How much? They stared blankly back. A man carrying a child on his shoulders stopped, mouth agape, and watched till we were out of sight.

Another fork ahead, we bought a watermelon to forestall any decision, sat in the dirt in our sweat-soaked clothes and ate in front of a friendly crowd, spitting our seeds into our hands, getting stickier and grubbier by the minute.

One of my children placed a straw hat on my head, warning me that I was already badly burned. Actually I felt flushed, not burned. The hat made my scalp sweat, still it was better than nothing. Once, long ago, our dog Happy rolled over on his back, stiff legs pointed skyward, suffering from heat prostration on a day far cooler than this one.

Where do we go from here? we asked with our slip of paper. A man drew us a diagram in the dust. Take the road to the left, his finger made a long line, then a circle to indicate Nanwutai. By now we had walked several kilometers. We couldn't be too far, though we still didn't see a mountain.

After a while we showed some women selling watermelons our precious slip of paper. "Nanwutai zai nar?" Where is Nanwutai?

They assumed we spoke Chinese, and their words and gestures rushed like a mountain stream quickly past. They frequently pointed in the opposite direction. Had we taken the wrong road after all? We still had forty something to go, that much Eli understood. It couldn't be forty minutes, nor forty kilometers. We knew from their reaction we were further than we ever imagined. Well, we could sleep out in the open, surrounded by fields and poplars and haystacks.

We trudged along. The road curved, then sloped shadelessly, steadily upward. Half-way up the hill, Adolph stopped and said, "I've had it, I'm hitching." None of us objected. Unfortunately the only traffic was bicycles.

Eventually a van approached, full of well-dressed, official-looking men. We showed them our slip, they pointed straight ahead, we refused to move. Finally they invited us in, clearly amused that we were walking all the way to Nanwutai. When we reached the top of the hill, we saw before us a road with no shade whatsoever curving through brilliant green rice paddies. And off in the distance was a range of dark, jagged mountains.

That was not our vision of Nanwutai. We expected a single small mountain rising like an aberration in the fields. Instead here was spectacular countryside overshadowed by a mountain range, and a van was bearing us across what would have been the most impossible, sunniest, part of our walk.

The men in the van let us out in the next village, telling us to continue going straight. There was little shade, the mountains appeared to be miles away, the temperature was still over 100 degrees, we were all beet red.

We came to a general store. The women behind the counter, excited to see us, turned on an electric fan and ran into the back room to bring out stools. We would gladly have stayed there till the following morning. Instead we stayed five minutes, bought a cake of soap and jars of pears and mandarin oranges, then reluctantly left, drawn by visions of monasteries and mountain streams.

I'm never sure of what to do when a pig is blocking my path, whether to calmly continue, ignoring him, or to wait till he goes somewhere else. I ignored several pigs that day; Sarah, I noticed, kept a spare rock in her hand. Pigs were everywhere, peering up at us from walled-in back yards, crossing the roads, wagging their tails and nuzzling each other.

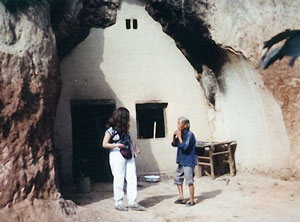

The dirt road wound upwards. Peeking into the courtyards, we could see that people lived in caves in the hillside. The facades were mud walls, each with a doorway and a window cut out. In one of those doorways an old woman and a little boy sat on a wooden bench. We walked across their yard and showed her our slip of paper, though we knew which way to go.

She was slight, no more than five feet tall. Her grey pants were rolled above her knees, blue cotton blouse untucked, grey hair pushed behind her ears, face expressive. She was glad to see us, understood we were hot, exhausted, and thirsty, and offered us something to drink. We hesitated, then nodded.

As she went in, I glimpsed the twilit interior of her cave, a pile of eggs, a wooden table, a stone oven, earth forming the walls. She dumped the contents of a large bucket into a tub, brought the empty bucket outside, and lowered it into a well a few yards from the cave door, down, down, so deep it had to be safe. Then she lugged the heavy bucket, probably two cubic feet of water, back to the door and handed us bowls which we dipped into the bucket, clear, sweet, the best water we'd ever tasted, a drink we'll always remember and we hope never regret. We doused ourselves, filled a flask, and, elated, continued our trek. This was not an easy walk, yet it seemed like the most beautiful one we'd ever taken.

Cyclists passed us, horse-drawn and donkey-drawn carts, small tractor engines with loaded flatbeds. An old lady approached me, one hand over her heart, the other indicating that I should put my hair up. I tied it in a knot behind my head, and she left smiling.

It would be a shame to have come to China and not to have done this, I kept exclaiming as we passed more rice paddies, haystacks, grapevines, corn fields, always the mountains in the distance. Adolph and I hobbled behind the others, my toe, his feet, the heat. A woman was bathing her daughter in a spring. We took off our shoes and submerged our listless feet. The water was cool, clearly coming from the mountains, though God knew where it had stopped along the way.

Cows, horses, goats, errant pigs, sun still beating down, we walked several more kilometers, every now and then showing our slip of paper, more for conversation, more out of disbelief at the distance.

Finally a thriving village, we'd been walking four hours. The townspeople followed us and stared as we made our way down the main street. The local English teacher introduced himself. Nanwutai? We had five kilometers to go, it would be dark, we should spend the night in his village. I would have, but the others were still lured by images of bathing in a mountain stream and sleeping in a monastery. Five more kilometers, we'd already walked about ten, and even in late afternoon it was damned hot. We bought another hat and banana ices, sipped from our flasks, and said we'd be back tomorrow. There was no shade as we trod the dirt road, avoiding pigs, nodding to the peasants walking or biking home from work carrying shovels, axes, mysterious packets. I tried not to notice the dead rat.

After another five kilometers, the mountain seemed at least a kilometer away. Adolph and I lagged way behind on the dusty road. A donkey was pulling a cartload of straw and manure, and I asked the young man perched on top if I could join him. He smiled and motioned me to hop on. But how could I do that to the poor donkey?

A truck rattled towards us in a cloud of dust, wheels waffling from side to side. We waved it down, showed the driver our slip of paper, and asked if we could climb into the back. He told us to get in; I couldn't figure out how. There were no projections for my feet. Adolph made a stirrup with his hands, and, scraping and bruising myself, I scrambled over the top. Adolph struggled in on his own; the man who had been riding back there boosted himself in with ease. Further ahead the driver stopped for Sarah, Eli, and Joshua.

In the cab of the truck were two men and a little boy; in the back, another man, the five of us, and a hundred watermelons.

When we reached the bottom of the mountain, they didn't stop, kept right on driving up the narrow dirt road, round hair-pin curves, the air becoming cool and fresh. Eli and Adolph were standing, gripping the wooden sides, Eli exclaiming, "I don't believe this, I don't believe that drop," as the old truck struggled up the narrow snaking road. I stood up, precarious, wondering if the side of the truck could tolerate my weight, and gazed down on a mountain range spotted with clouds.

The man in back with us stood calmly in a corner, enjoying the breeze and watching us with amusement. He offered us cigarettes, lit one up for himself.

The trip to the top would probably have taken us two days on foot. It was dusk when we finally stopped. The floor was sticky with watermelon juice; our cameras, sandals, hats, bathing suits, and toilet paper roll were mixed in amongst the melons. We gathered our possessions and clambered out, ready to lie down on the floor of any monastery.

We tried to hand the driver 20 yuan. He shook his head no, climbed into the back of the truck, selected a melon, sliced it with our jack-knife, and we sat on the ground with several construction workers who were repairing the road. Our hosts passed around the melon, using our newspaper as plates, refusing any for themselves.

The monastery was at the top of some rough stone steps curving up the mountainside. We said good-bye, but the watermelon men climbed with us. About half-way up we came to a small cave, and they motioned us to come in with them and sit on the rocks. I pointed upwards, towards the monastery and mimed that I wanted to go there and sleep. They continued to beckon; I continued to stand. The truck-driver gestured with his hands, imitating a balloon popping. At that moment there was an explosion, and debris rained down around me. Workers were dynamiting the mountain above.

A monk came down from the temple; apparently they didn't take guests. Adolph and the boys wanted to sleep in the cave, Sarah and I wouldn't, the watermelon men were adamant that we couldn't. We made our way down the steep uneven steps, already becoming treacherous as the sun set.

There were sand piles near the truck, probably used for road construction, and we considered sleeping there until Joshua mentioned that they might start blasting again in the morning. Climbing in and out of the truck wasn't easy, and Adolph thinks he broke a rib. Still we were euphoric. We drove down in darkness, stars intense, mountains outlined by their light, air by far the purest we'd breathed in China.

Half-way down the mountain was another monastery, silent in the dark, candlelight glowing through the upstairs windows. Our driver went in, and we could hear shouted conversations, see shadowy figures converging. The man in the back remained with us. "Chinese and Americans the same," he said several times in Chinese, delighted with the idea.

After fifteen or twenty minutes our driver returned, and we continued downwards into heat and humidity till we came to a tiny hotel. The men led us through a general store on the first floor, into the back yard, and up concrete steps to the sleeping quarters. The hotel had three small guest rooms lit by naked light bulbs. The beds were made by placing a straw mat on a board supported by two chairs at each end. Filmy white mosquito netting hung from the ceiling. 18 yuan, $6.50 for the five of us.

The manager was a gentle old man. He filled a basin with hot water, and he and the watermelon men watched intently as we squatted on the floor to wash. I doubt I've ever looked grubbier in my life; my white slacks and tee-shirt were layered with grime. Even my teeth were gritty.

The watermelon men led us back downstairs into the street and around a dark corner, crowds gathering as if we were Martians. We came to a mud house, radio blasting a Chinese play or soap opera. Someone brought low stools outside for us, then a pan of cold fritters. The curious crowd watched us eat. Where were we from? What were our names? What was our relationship to each other? How old were we? Why weren't we wearing watches? And I noticed that almost everyone had a watch on his wrist. I searched through my purse and found a small plastic digital clock which I handed to the truck driver, indicating he should keep it. No one would take it. Next they brought us five bowls of soup; it tasted like hot vinegar.

When we finished eating, the watermelon men escorted us back to the hotel.

The excited manager showed us the outhouse, walking through the dark yard to a tiny shelter in the back, unlit, no way to tell where the hole was, very possible to end up in it. Next trip to China I'll bring a flashlight.

He brought us back upstairs and filled two basins, one for soapy water, one for rinsing, watched till we finished, then emptied the water by sprinkling it onto the floor, perhaps to cool the place down. If so, it didn't work.

Sarah and I shared a room, both of us exhausted, over-heated, and wide awake. I poured the hot water from the thermos into a cup and sipped it, let it cool a few minutes, doused myself. I still couldn't sleep. We felt a breeze when we stuck our heads out the window, full moon shining over haystacks in the back courtyard. We couldn't spend the night with our heads out the window. We pushed Sarah's "bed" in front of the door to hold it closed and lay naked and sleepless on our mats. I sipped more water, again doused my body, then reached out in the dark to put the cup on the night table. I missed.

We could hear the breeze and the rush of an unseen mountain stream. Finally we dressed and felt our way past men sleeping on the hallway floor and down the cement steps in search of a breeze and a stream. The hotel door was padlocked. We went back up and lay down on the concrete balcony, which at least was cooler than our room.

The manager discovered us there at five and awakened us to give us mats and pillows. People were sleeping on mats right next to us and on the dusty road below. I now understand with a different kind of knowing why so much of life in the summer is lived outside.

We weren't looking forward to walking back to the bus stop, at least fifteen kilometers under the hot sun. In fact we were delighted to see grey skies when we awoke.

We started out early. The thunder we heard in the distance was only workers blasting near the cave where we hadn't slept. Women washed their clothes and their children in the stream that rushed alongside the road in a man-made canal. I stubbed my broken toe on a rock. It was so swollen it led all my other toes and was always the first to hit any obstruction in my path. I limped to the stream and submerged my feet, watermelon rinds speeding past my ankles. Perhaps we could hitchhike later, for now there were only donkey carts, bicycles, tractor engines, and pedestrians.

After five or six kilometers, we were in the thriving village again. We ate a late breakfast of noodles flavored with horse radish, then continued to walk until we saw a mirage, a bus. Feeling like five grimy wrecks, we stood in the middle of the road and waved our arms. The peasants welcomed us in and even gave us their seats.

[Rosenblatt Gallery] [Suzanne home page] [Writing portfolio] [Travel journals] [China]

[Visual Art portfolio] [Feedback]

Copyright © 2002 Suzanne Rosenblatt. All rights reserved.

( No pathinfo hits since 10 June 2002)